Overview

In 1828, three years before The University of Alabama opened its doors to students, the institution purchased its first enslaved person, a man named Ben. Alongside many other unnamed enslaved people of African descent, Ben helped to erect the first buildings on campus, but he was also integral to the success of UA in its early years. In fact, President Basil Manly spoke openly about the University’s reliance on enslaved labor in his 1840 President’s Report declaring that "we could not do business for a single day without servants." Whites often used "servant" to mean "slave" at this time, in effect erasing the brutality of claiming ownership of another person. Relying on enslaved labor to make campus function was not a surprising turn of events – before 1865 most institutions of higher education in the United States, and especially those in the South, purchased or hired out enslaved individuals from their legal owners. The University of Alabama was no different. Moreover, profits from slavery were the foundation on which the state’s economy rested, and so were the source of financing used to establish, build, and maintain the state’s flagship college.

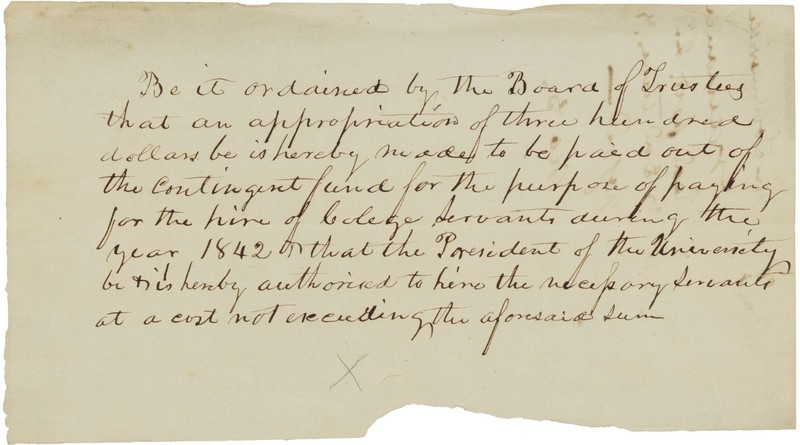

As an institution of higher learning in the South, The University of Alabama served the elite white male youth of Alabama and surrounding states. The curriculum was one of general classical education – students studied philosophy, English literature, history, chemistry, geology, mathematics, and engineering. The young men who entered UA as students were schooled in pro-slavery arguments and rhetoric from faculty and invited speakers alike. They also got first-hand experience in meting out violence to enslaved people. But many of them did not need these additional lessons because they had grown up in an environment where whites assumed command and control of African Americans through legal, physical, and psychological means. Students were prohibited from bringing enslaved people to campus to serve as personal attendants, but most of the faculty brought enslaved people to UA to serve their households. In addition, the University purchased at least four enslaved men between 1828 and 1853. The vast majority of those who labored on UA’s campus, however, were hired from enslavers in Tuscaloosa and the surrounding area.

The practice of "hiring out" or "renting" enslaved people was commonplace in the U.S. South, and especially in urban areas like Tuscaloosa. In order to maximize profits, enslavers in towns and cities, who did not need the labor of all the people they owned, leased their skilled domestics or craftsmen to other white people or institutions. They negotiated prices with leasees, came to agreements about where the enslaved person would be housed, and arranged who would be responsible for food and clothing for the duration of the contract. Contacts were always made between enslaver and leaser, but enslaved people sometimes arranged with their enslavers to keep a small portion of the money from their hire. While white men often negotiated these arrangments, a significant number of white women hired out enslaved people in this manner. At UA, one of the most prolific leasers of enslaved workers was Isabel A. Pratt. Another was her sister, Mary Drysdale. Susan B. Comegys, Salina Riddle, and Anna S. Prince were among the other white women who hired out enslaved men like Peter, William, York, Crawford, and Wash to the University.

By the time students awoke in the morning, enslaved men had lit the fires and hauled water to the rooms from Marr’s Spring or, if they were fortunate, one of the wells closer to the dormitories. They made the beds and swept the floors and passages. When students went for breakfast or dinner they ate fare prepared and cooked by enslaved people. Enslaved men waited on them in the dining halls. They ran errands for students, helped professors set up classroom experiments, and were generally at the beck-and-call of faculty and students alike. They cleaned the dormitories, built and repaired broken furniture, maintained buildings and erected new ones. Enslaved women were not allowed to enter the college buildings, but they still worked in the homes of UA professors and in the President’s Mansion. Enslaved people were beaten and whipped by students and faculty for the smallest perceived indiscretion or simply for entertainment. Some were sexually assaulted. Others became ill and died and were buried on campus. All were essential to helping The University of Alabama flourish in its first decades.

But the women and men who were enslaved on UA's campus also had lives beyond those prescribed for them by their enslavers or the people who had hired them. They formed families, birthed children, established side work, and demonstrated their myriad skills at every turn. Sometimes they ran away. At other times they spoke truth to power in spite of the consequences. And at still others they worked to carve out time away from the watchful eyes of the college president, faculty, and students at The University of Alabama. While not all are named and accounted for in the records, they all left their mark on this campus and this institution.