Peter

Upon his death in 1892, Peter Madary was the patriarch of a well-established African American family in the Castle Hill District of Tuscaloosa. By 1870, he, and his wife Betsy, were the parents of eight children, they owned a parcel of farmland, and he was among the first group of men of color in the county registered to vote. All records of his early life, however, denote him as Peter Pratt, the name given to him by his enslavers, University of Alabama professor Horace S. and his wife Isabel A. Pratt. Freed from enslavement at approximately forty-five years old, Peter’s story provides an exceptional opportunity to explore both his experience of slavery on the university’s campus, as well as how he envisioned and pursued freedom in the decades after the Civil War.

Archival records reveal nothing concrete about Peter’s birth or early life. He was most likely born in Georgia sometime between 1820 and 1825. His mother was possibly an enslaved woman purchased by Horace Pratt or one that joined his household through marriage (first to Jane Wood in 1823 and later Isabel Drysdale in 1832) as part of the property Horace’s wives brought to their union. A reasonable guess, considering her later role in hiring him out, however, suggests that Peter was the child of an enslaved individual Isabel inherited from her mother or sister, among whom only a few names are known. Unfortunately, guesswork is too often all researchers can rely on when discussing an enslaved individual’s adolescence. It was not until 1840, when Peter was roughly twenty years old, that his name appeared for the first time in the written record.

Peter arrived in Tuscaloosa in 1837 when Horace Pratt accepted a position to serve as a Professor of English Literature at the University of Alabama. He was among several enslaved individuals, including William, Edward, James, and Jim, who accompanied Horace’s wife, children, and sister-in-law to campus. The family took residence, according to early drawings, just northeast of the early university buildings, approximately where Fresh Food Company and Rodgers Library are today. Peter’s life soon after became consumed by the hustle and bustle of campus activity waking with or before the morning bell, observing throughout the day the commotion and antics of the students, and working alongside the other enslaved individuals who ensured the university’s successful operation in its six-year infancy.

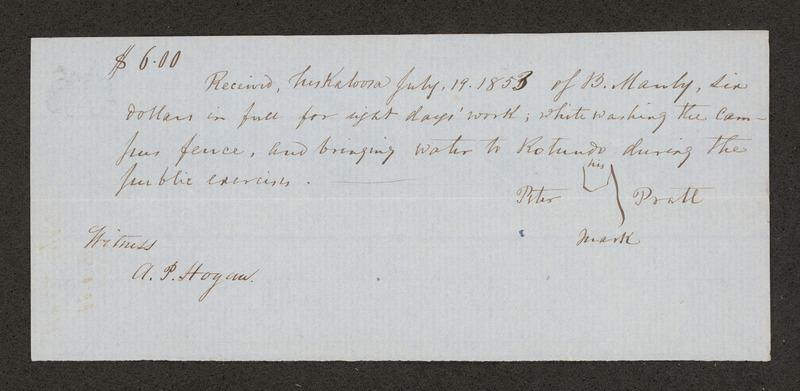

During his years of service at the university, Peter spent around ten hours every day attending to the state of the dormitories. Responsible for typically nineteen or more rooms daily, his tasks for each included bed-making, sweeping, lugging coal up from the cellar, and obtaining between one or two buckets of water, sometimes from a distance of "more than 200 yards" away. Strict conditions required he perform these duties quickly allocating him “less than half an hour” per room. Although no records indicate he ever received punishment, any misbehavior (perceived or real) could evoke the discipline of both the students and the administrators set to oversee him. In addition to his daily requirements, and especially during the summer, he was also required to spend "some two to three hours per day" assisting with improvements about the campus, including planting trees, whitewashing buildings inside and out, refortifying wells, repairing and painting fences, and various other projects. On at least one occasion, July 19, 1853, however, records show he did negotiate an earning for himself of $6 by providing eight days of labor "white washing the campus fence" along with "bringing water to the Rotunda during the public exercises." Unfortunately, whether Peter remained working on campus after 1853 or Isabel directed his labor elsewhere remains unknown. His name is never mentioned in campus records again.

Peter’s life outside of his campus responsibilities, like that of millions of enslaved individuals, received little attention from the administration leaving further speculation about the dates of his marriage and the births of his children. The only known record of Peter’s marriage, for instance, is an entry in President Manly’s diary on July 25, 1845, stating that he "gave him leave to go to Windham's Springs to see his wife, who is in the neighborhood of that place with her mistress, Mrs. Fiquet." Unfortunately, still less information is known about Betsy herself and the conditions she faced during enslavement. "Her mistress," Mary Ann Foster Fiquet, followed her merchant uncle (Charles M. Foster) to Tuscaloosa in the 1830s. Shortly after her arrival she married a local tailor and plantation owner, C. J. Fiquet. There is no evidence that Peter ever worked for the Fiquets or Foster (or that Betsy worked at the university) but Manly did hire out a man he enslaved, Augustus, to work at C. J. Fiquet's clothing store in July 1845. In addition, the university routinely dealt with Foster buying items like shoes for enslaved workers. It is not out of the realm of possibility therefore that Peter found means of introduction to Betsy through her enslaver’s association with the university. Census records and the slave schedules of 1850 and 1860 provide the only other records to help identify her early life story. They indicate her birth occurred sometime between 1824-1830 in Virginia. They also suggest that she bore their first seven children (Peter Jr., Ellen, Susan, Cornelia, Coleman, Dudley, and Rosa) while enslaved, although the exact dates of their births remain unknown. She likely raised her children alone during this time as no evidence supports Peter and Betsy lived together until after the Civil War.

Peter and Betsy acted quickly to capitalize on the opportunities of their freedom from bondage. In 1865 Peter moved to stay with Betsy and their children seizing a right that enslavement previously denied them. He registered to vote at the first opportunity granted him on June 21, 1867. That same year, on Christmas Eve, the couple bought their own property, for which they paid $120. They welcomed the birth of their final child, a son named Jordan, the next day. According to the 1870 census, during these years Peter worked at a local factory while Betsy managed the household. Five of their children (Susan, Coleman, Dudley, Rosa, and Jordan) attended school. Peter decided to pursue farming as his main occupation at some point over the next decade. The Agricultural Census for 1880 attests to Peter and Betsy possessing fourteen acres of tilled land, two mules or donkeys, and an estimated farm production value the year before of $160 dollars. Their pursuit of economic independence, land ownership, political participation, and the education of their children was among the myriad of ways in which the couple, like millions of other formerly enslaved individuals, insisted upon their rights and vision of freedom and citizenship.

These hard-won accomplishments came against a backdrop of white violence and intimidation wrought by the backlash to freedom across the Reconstruction South. As early as February 5, 1867, while still living on the Fiquet property, circumstances prompted Peter to file a complaint with the Freedmen’s Bureau in an attempt to receive justice for his eldest son. Four days earlier William Fiquet, son to Betsy’s former enslavers, confronted Peter Jr. "about a girl wasting water." Peter Sr. claimed that after exchanging blows William "stuck" his son "with a stick." Two days later Peter Jr. endured further violence during an attempt to retrieve his clothes. The Fiquet’s other son, Charley, led Peter Jr. "from the kitchen to the stable" and proceeded to beat him with a stick. No records indicate whether or not the Bureau agent responded to Peter Sr’s accusation. However, the attack against Peter Jr. likely incentivized Peter and Betsy to purchase property later that year in an attempt to remove themselves and their children both from white oversight and potential violence.

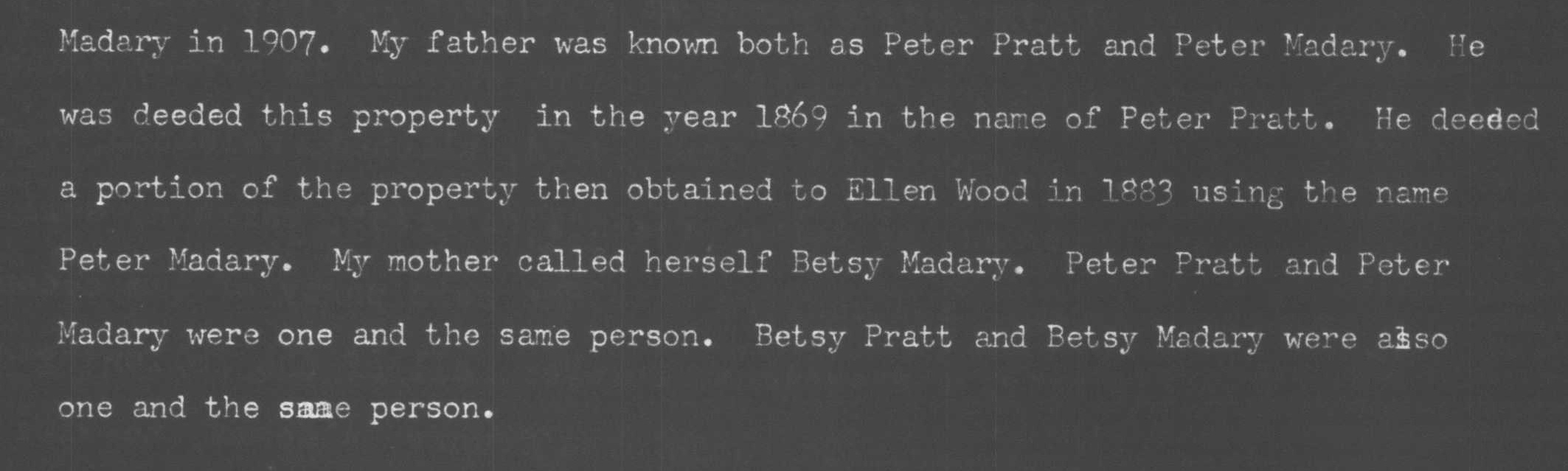

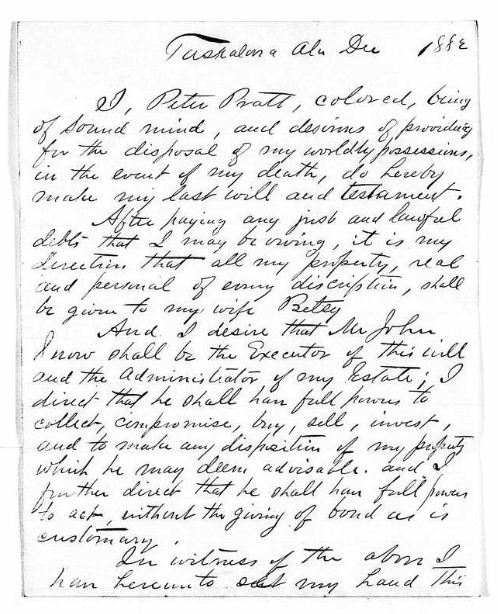

Peter and Betsy are listed with the last name "Pratt" in all records preceeding 1883. Peter even began his will by referring to himself as "I, Peter Pratt" in December 1882. Soon after however, the couple chose a different surname. We know about the change because the couple sold a portion of land to their daughter Ellen for $5 on February 5, 1883. On the deed, although referred to at the top as Pratts, both Peter and Betsy signed their marks, a small x for each, alongside the Madary last name. Why they chose to make the change or picked that specific surname is unclear as no documentation exists to explain their motivations. Like numerous formerly enslaved individuals they may have considered changing their last name another vital step in the process of asserting their freedom. On March 9, 1950, their youngest son Jordan, while attempting to sell the final remnants of their property, provided the only testimony on the affair: "Peter Pratt and Peter Madary were one and the same person. Betsy Pratt and Betsy Madary were also one and the same person," he explained. Peter and Besty proceeded to use the Madary last name interchangeably, sometimes even alongside the Pratt surname too, until their deaths. Their male children, however, are only ever recorded under various spellings of Madary in their adulthood.

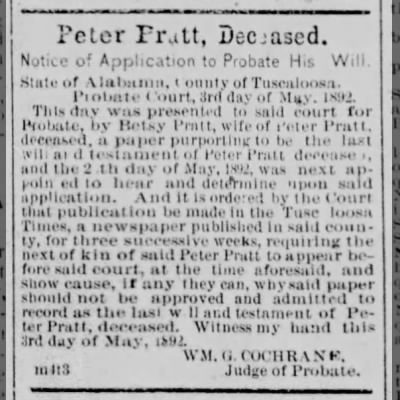

Peter died on March 30, 1892. Betsy outlived him by almost two decades. She was survived by four children (Coleman, Jordan, Ellen, and Cornelia) and seventeen grandchildren upon her death on December 24, 1911. Some of the couple's descendants stayed in Tuscaloosa while others followed the millions of African Americans heading North and settling in Ohio as part of the Great Migration. Both Peter and Betsy were buried in Evergreen Cemetery in Tuscaloosa. Students and visitors pass regularly on their way to Bryant-Denny Stadium without knowing their resting place lies in its present looming shadow.

Profile written by Briana Weaver

Peter Madary

Follow the link above to view the database entry