Moses

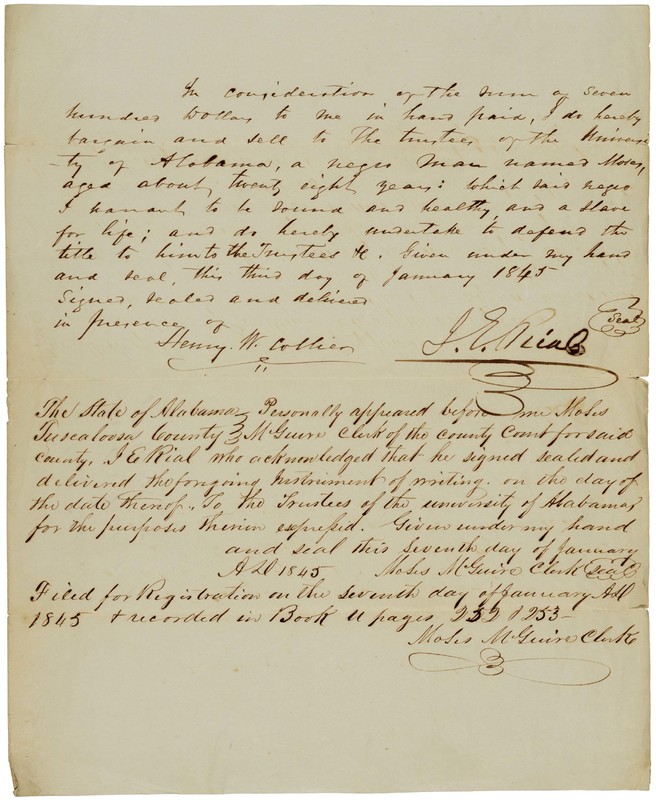

Moses was an entrepreneurial family man. Skilled in the "good use of tools" he raised chickens to supplement his family’s food supply and possibly to earn some small amount of money in addition to the many other tasks he performed at UA. One of a small number of men enslaved directly by The University of Alabama, Moses was "aged around twenty eight years" when President Basil Manly facilitated his purchase for $700 on 3rd January 1845.

The kinds of work Moses performed were myriad: he plastered walls, set up the fire grates in the tutors’ rooms and dormitories, repaired outbuildings, fixed up Prof. Stafford’s potato cellar, made a dredging machine to rake shells up from the bottom of the Black Warrior River, improved Prof. Garland’s Athenaeum, built platforms and fixtures at the observatory (Maxwell Hall on Stadium Drive), mended chimneys on the dormitories, and hauled sand and water. Moses also assisted Prof. Garland (before Garland became UA’s president), in the classroom, repairing and adjusting apparatus, working on electric telegraph fixtures and setting up the blackboard. He helped beautify campus too, planting trees and hedges and repairing fences and pathways. Later that same year, Moses worked alongside enslaved carpenters, William and Willis, and another unnamed enslaved youth to finish the newly constructed Jefferson building, laying 30, 750 shingles on its roof. Moses was also part of a team that whitewashed the dormitories in the summer of 1851. By December of 1853 Moses was working alongside Prof. Tuomey "to attend to the Laboratory building."

In addition to the everyday work needs of campus, Moses also repaired buildings following acts of student vandalism or accidents like fire. In March 1846, students stripped shingles off the roof of one of the buildings and Moses was the one to fix the damage. When a spark from Prof. Barnard’s chimney set his home alight in October that same year, Mr. Boyle (a white laborer often employed by UA) and Moses rushed "through the flames" into the building to begin the work of extinguishing the fire before students arrived with buckets of water to put out the conflagration. A few days later, Moses and Boyle repaired the damage to the roof using old shingles.

Like so many of the enslaved workers on campus, Moses was subjected to violent beatings by students. Some of these attacks were recorded in the pages of President Manly’s diaries. In March 1846, just a few months after Moses was purchased by the university, B. F. Stafford, assaulted him in the Common Hall (now Gorgas House) with a table fork, piercing his arm with the weapon. One year later, in February 1846, Robinson struck Moses' right arm with such force that Moses was unable to return to work. Manly hired-out another enslaved person from a local Tuscaloosa resident to take over Moses’ duties while he recovered. Students also intimidated Moses at his residence. In 1850 a drunken “party of students” went into his yard, stole the fowls Moses was raising, "and made some show of violence" The following year, Moses was "beaten...very much" by Wilson J. Walthall and Robert Cochran. The students had stolen turkeys from President Manly and suspected Moses of informing on their crime. They lured Moses to the Jefferson dormitory on the pretense of cleaning their boots before binding his hands, turning out the lights, and first beating him with sticks before whipping him in front of “nearly every one in the building.” These actions were intended not only to hurt but also to humiliate Moses. When questioned by Manly about their behavior most of the students denied the accusations. They viewed their power over Moses as merely an extension of their rights as students of UA. As President of the institution that enslaved Moses, Manly no doubt felt that the students disrespected his authority when they assailed Moses. After all, they had harmed, what in Manly’s view, was university property, and indeed he charged the students for money spent hiring Moses’ replacement. Almost all of the students involved in the attack were dismissed from UA. Whether their greater crime was beating Moses or challenging Manly’s position and honor is unclear.

Overt violence was not the only way whites attempted to keep enslaved people in check; fears for family and loved ones were frequently invoked, including by President Manly. Moses allegedly drank alcohol, something of which Manly disapproved. He threatened Moses with being sold away if he did not stop drinking. Given that his wife and at least one daughter lived with him on campus, this was no idle warning. Enslavers often used the looming specter of family separation to control those they enslaved and Manly was no different.

The beatings, the constant surveillance, the hard work of maintaining campus, and the never-ending demands from students took a toll on Moses’ health. In the summer of 1850, and again in October 1851, he needed medical assistance. Rather than disrupt the workday, or give Moses time to recover by relieving him of his duties, President Manly hired Dr. Reuben Searcy to "visit at night" when he delivered medicine to improve Moses’ outlook.

For all that we know about Moses – and so much is still unclear – there are even fewer references to his wife and children. In 1848 Manly noted in his annual report that Moses had a "wife and family living on the premises" but who this woman was, or how many people constituted their family remains a mystery. However many children the couple had, three years later one of them was deathly ill. In an aside in a November 1851 diary entry about a drunk and disorderly student named Alfred James, President Manly noted that a "child of Moses was dying." By this time Moses and his family appear to have been living at Prof. Stafford’s residence on campus. Whether he lost a daughter or a son that night, or shortly thereafter, this was yet another painful experience that Moses, and his wife (whose name is unknown) had to bear. The same student "or some one else" (according to Manly) had fathered a child with "a girl of Moses" – either his daughter, or his wife. The casual way that Manly discusses the subject belies the threats of sexual assault that enslaved women and girls on campus were exposed to at all times. The "girl of Moses" was not the only enslaved woman to have her bodily autonomy threatened.

Sometime in the mid 1850s the university sold Moses. Probably around forty when they made the sale, he had labored at the institution for at least a decade. He may have continued to work on campus, as his new enslaver was Prof. Stafford. He almost certainly stayed in Tuscaloosa, because in 1857 Prof. Stafford and his wife Maria left UA to take charge of the Alabama Female Institute, a college of higher learning for white women in the city. Moses was one of twenty people enslaved by the couple in 1860. It is possible that his wife and any surviving children were among that number, but the slave schedule for the 1860 census is not specific enough to be certain. The 1866 U.S. Census, taken in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War, provides some clues as to Moses' life post emancipation. A "Moses Stafford" (the last name of his last enslaver) is listed in the "Colored Population" schedule for Tuscaloosa County. While many freed people did not take last names connecting them to their former enslavers, some did, or at least did so initially, so Moses may well have been known by this name in the mid-1860s. The census is frustratingly vague about the occupants of this Moses' household. Either Moses or the person taking the census placed his age in the 60-70 bracket, putting about ten years on the man who labored at UA. There was a woman in the 50-60 age range, another woman aged between 20 and 30, and a girl under the age of ten. These are probably Moses' wife and daughter (one of whom was the "girl of Moses" referred to in Manly's diary), and his granddaughter. Although their names or anything more specific about them remain unknown, we know that these members of Moses' family lived to see freedom, and did so together.

Profile written by Jenny Shaw

Moses

Follow the link above to view the database entry