Binkey

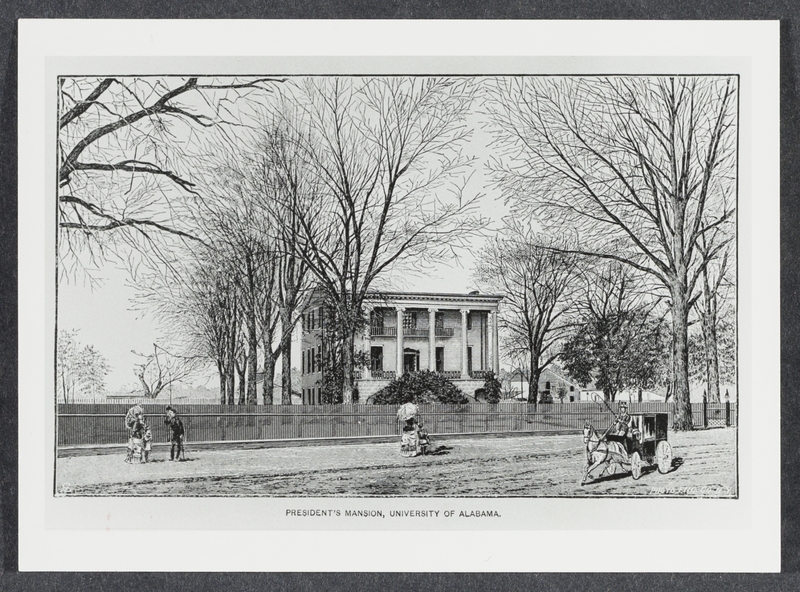

Binkey's strong sense of self and desire for independence were set from a very young age. She began her life on The University of Alabama's campus in March 1840 when her mother, Mary, gave birth in President Manly's home and spent her first twenty-five years enslaved to Manly, growing up in the newly constructed President’s Mansion alongside, but unequal to, Manly’s white children. She was no doubt engaged in the kinds of smaller tasks assigned to enslaved children beginning from around the age of six including assisting enslaved domestics with housework and running simple errands. But despite being born on campus, and her long-term enslavement by the Manlys, Binkey did not work consistently at UA. Hired out to various white Alabamians, her life story reveals a lot about the kinds of behavior expected of enslaved girls and the ways that Binkey refused to comply. It also provides a glimpse of her attitudes towards freedom at the end of the Civil War.

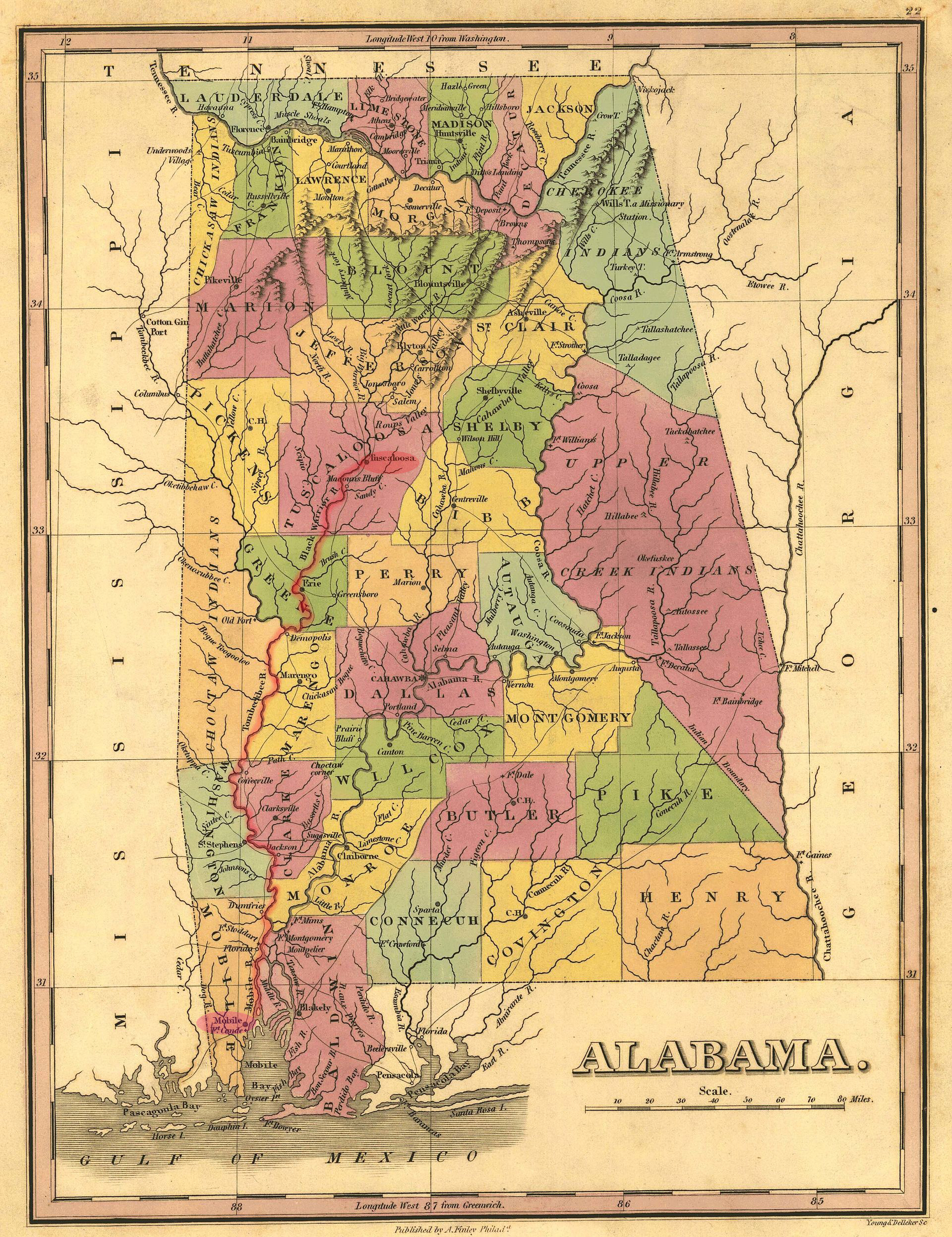

At the age of nine Binkey was hired out for the first time. According to the terms of the December 1849 agreement, she was to work for "Mrs Hopkins" the wife of a Tuscaloosa merchant. The Hopkins were to "clothe her, lodge her, pay her taxes" and give Manly "$24 for her year’s services." Mrs Hopkins would have tasked nine-year-old Binkey with a whole host of jobs, most likely washing, sweeping, laundry, running errands, and answering every desire of her mistress. She did not last long in this position. By March 1850, just three months after arriving in the Hopkins home, Binky was accused of stealing and discharged.

Binkey did not remain back at the President’s Mansion for long. Just ten days after she returned from the Hopkins' residence, Manly hired her out to Mr. Boyle, a white laborer who frequently worked on UA construction and repair projects alongside enslaved laborers. Hired at $3 a month, this time Manly was to "find her clothes." Once again, Binkey was back at the President’s Mansion in short order. On 1st April 1850 "Boyle sent her home, for stealing and fighting." She was with him not quite three weeks.

It seems apparent that Binkey, barely ten years old, did not act with the deference elite whites expected of young enslaved girls. Whether she was guilty of theft or fighting is immaterial, although both were tried and tested strategies that enslaved people employed as ways to challenge an enslaver. By the end of the year, Binkey was hired out once more "to stay a year with Mrs. Hill." Things appeared to work better this time around. Not only did Binkey remain with Mrs. Hill for the whole term of the contract, but her services were subsequently requested by Mrs. Clitherall who hired Binkey in 1852 and took her to Mobile, almost 200 miles from Tuscaloosa. The work she performed for these women was probably in the domestic realm. She might well have made herself indispensable, as Mrs. Hill was reluctant to part with her services in 1851. But regardless of how well, or how poorly, she worked, by May 1853 Binkey was back in Tuscaloosa. While the precise circumstances of her return are unclear, she was ill. Perhaps Mrs. Clitherall did not want to pay rent on a sick laborer. Or the risk of contagion may have spurred her to direct Binkey back to Tuscaloosa. Either way, she was sent back to the place where she was born.

Manly’s diaries are silent on what work Binkey performed upon her return. She was thirteen at the time and might have continued to perform domestic chores alongside Sabra and others in the President’s Mansion. But it seems more likely that she was sent to work on a plantation that Manly purchased near Foster’s Ferry Road, southwest of the city. If so, this place was probably where she met her husband, an enslaved man named Andrew in charge of Manly's hogs. Together the couple had three children – Elizabeth, Julia Ann, and Larrey – before their relationship broke down.

The end of the Civil War brought freedom for Binkey. Initially, she was among the 28 formerly enslaved people who signed a contract on 20th June 1865 to continue to work on Manly's plantation. But very quickly Binkey gave up on the "ten average acres of corn" the agreement was supposed to secure her. An end to slavery did not bring with it an end to the violence she could expect from white people. On Friday August 25th, Binky left the plantation following an altercation with Manly’s son, James. When fire broke out at a neighboring plantation at the end of the workday, James ordered his workers, whom he described as "the negroes" to stay put rather than return home for dinner. When they refused, James "came home, intending to punish them." He encountered Binkey first – but when he beat her, she resisted and fought back. Fleeing from the Manly property, she headed straight for "her mother's house" in Tuscaloosa. One week later, twenty-three other workers joined her exodus. No longer with Andrew, her young children arrived shortly thereafter. Mother, grandmother, daughters, and son were now reunited.

What happened to Binkey and the rest of her family after this moment in time is currently unknown. Finding her, or any of her children, in the 1870 census, for example, is a tall task, because we do not know the last name she took upon freedom. Some enslaved people were given the names of their enslavers, while others chose a new last name, sometimes one that underscored their free status. But although we do not know with any certainty where she made her home, we do know that at least in her first year of freedom she refused to accept violent and unacceptable treatment from her employer, she perhaps inspired others to act as she had, and she got to be with her family, in the city where she was born, no small achievement for a woman born into slavery on The University of Alabama campus.

To read a transcription of the diary entry above, click here.

Binkey

Follow the link above to view the database entry